|

|

|

|

1945.8.9 At 11:02 a.m. August

9, 1945 |

| August 9, 1945. 11:02 a.m. Bockscar, the B-29 bomber carrying

a plutonium-core atomic bomb and commanded by 25-year- old Major Charles Sweeney,

dropped its deadly cargo over Nagasaki from a height of 9,600 meters. Like the

primary target Kokura, Nagasaki was overcast that morning. With barely enough

fuel remaining to reach Okinawa, Major Sweeney and his crew had to pinpoint their

target in the course of only one run over the city. By chance a crack opened

in the clouds, revealing the industrial zone stretching from the Mitsubishi sports

field in Hamaguchi-machi to the Mitsubishi Steel Works in Mori-machi and automatically

designating this as the bombing target. The actual explosion, however, occurred

some five or six hundred meters to the north over a tennis court in Matsuyama-machi.

The details of the explosion can be summarized as follows. |

|

|

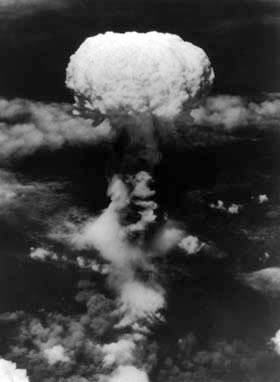

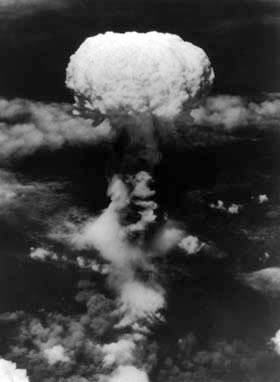

| The mushroom cloud seen from an American aircraft |

The

mushroom cloud seen from an American aircraft The

mushroom cloud seen from an American aircraft |

| Nagasaki two days before the atomic bombing |

Nagasaki

two days before the atomic bombing Nagasaki

two days before the atomic bombing |

| Nagasaki three days after the atomic bombing |

Nagasaki three days after the atomic bombing Nagasaki three days after the atomic bombing |

| The atomic bomb mushroom cloud over Nagasaki on August

9, 1945 |

Photograph

by Hiromichi Matsuda Photograph

by Hiromichi Matsuda |

Known

as Urakami, the district around the hypocenter (ground zero) area had been populated

for centuries by Japanese people of the Roman Catholic faith. At the time of

the bombing, between 15,000 and 16,000 Catholics - the majority of the approximately

20,000 people of that faith in Nagasaki and about half of the local population

- lived in the Urakami district. It is said that about 10,000 Catholics were

killed by the atomic bomb. Although traditionally a rustic isolated suburb, the

Urakami district was chosen as the site for munitions factories in the 1920s,

after which time the population soared and an industrial zone quickly took shape.

The district was also home to the Nagasaki Medical College and a large number

of other schools and public buildings. The industrial and school zones of the

Urakami district lay to the east of the Urakami River, while the congested residential

district of Shiroyama stretched to the hillsides on the west side of the river.

It was over this section of Nagasaki that the second atomic bomb exploded at

11:02 a.m., August 9, 1945. The damages inflicted on Nagasaki by the atomic bombing

defy description. The 20 machi or neighborhoods within a one kilometer radius

of the atomic bombing were completely destroyed by the heat flash and blast wind

generated by the explosion and then reduced to ashes by the subsequent fires.

About 80% of houses in the more than 20 neighborhoods between one and two kilometers

from the hypocenter collapsed and burned, and when the smoke cleared the entire

area was strewn with corpses. This area within two kilometers of the hypocenter

is referred to as the "hypocenter zone." The destruction caused by

the atomic bomb is analyzed as follows in Nagasaki Shisei Rokujugonenshi Kohen

[History of Nagasaki City on the 65th Anniversary of Municipal Incorporation,

Volume 2] published in 1959. The area within one kilometer of the hypocenter:

Almost all humans and animals died instantly as a result of the explosive force

and heat generated by the explosion. Wooden structures, houses and other buildings

were pulverized. In the hypocenter area the debris was immediately reduced to

ashes, while in other areas raging fires broke out almost simultaneously. Gravestones

toppled and broke. Plants and trees of all sizes were snapped off at the stems

and left to burn facing away from the hypocenter. The area within two kilometers:

Some humans and animals died instantly and a majority suffered injuries of varying

severity as a result of the explosive force and heat generated by the explosion.

About 80% of wooden structures, houses and other buildings were destroyed, and

the fires spreading from other areas burned most of the debris. Concrete and

iron poles remained intact. Plants were partially burned and killed. The area

between three and four kilometers: Some humans and animals suffered injuries

of varying severity as a result of debris scattered by the blast, and others

suffered burns as a result of radiant heat. Things black in color tended to catch

fire. Most houses and other buildings were partially destroyed, and some buildings

and wooden poles burned. The remaining wooden telephone poles were scorched on

the side facing the hypocenter. The area between four and eight kilometers: Some

humans and animals suffered injuries of varying severity as a result of debris

scattered by the blast, and houses were partially destroyed or damaged. The area

within 15 kilometers: The impact of the blast was felt clearly, and windows,

doors and paper screens were broken. Wall clock found in Sakamoto-machi about

1 km from the hypocenter. The hands stopped at the moment of the explosion: 11:02

a.m. The injuries inflicted by the atomic bomb resulted from the combined effect

of blast wind, heat rays (radiant heat) and radiation and surfaced in an extremely

complex pattern of symptoms. The death toll within a distance of one kilometer

from the hypocenter was 96.7% among people who suffered burns, 96.9% among people

who suffered other external injuries, and 94.1% among people who suffered no

apparent injuries. These data show that the deaths occurring immediately after

the atomic bombing were due not only to burns and external injuries but also

to severe radiation-induced injuries. The late medical effects of atomic bomb

exposure include "keloid" scars, atomic bomb cataracts, leukemia and

other cancers and microcephaly (small head syndrome) due to intrauterine exposure.

Although aware that the atomic bomb had the power to instantly kill or injure

all people within a radius of four kilometers, the authorities were unable to

determine the death toll and number of injuries in Nagasaki. Still today there

is no accurate data on the number of people who died. A variety of factors contributed

to this lack of information, such as the paralysis of administrative functions

in the aftermath of the bombing and the inability of the postwar government to

initiate a proper investigation. Another obstacle was the enduring nature of

disorders related to atomic bomb exposure. A progressive increase can be expected,

therefore, at whatever point in time calculations are made. There are countless

cases of people who suffered injuries on August 9 and died after fleeing to areas

outside Nagasaki city and prefecture, only to be registered as dying of causes

other than the atomic bombing. Because of the lack of knowledge about radioactive

contamination, meanwhile, many radiation deaths were attributed to diseases.

The Nagasaki municipal government officially adopted the figure of "more

than 70,000" deaths on the basis of information from population surveys

and the estimate made by the Nagasaki City Atomic Bomb Records Preservation Committee

in July 1950. Said the committee in its report: "73,884 people were killed

and 74,909 injured, and 17,358 of the deaths were confirmed by post- mortem examination

soon after the atomic bombing." Known

as Urakami, the district around the hypocenter (ground zero) area had been populated

for centuries by Japanese people of the Roman Catholic faith. At the time of

the bombing, between 15,000 and 16,000 Catholics - the majority of the approximately

20,000 people of that faith in Nagasaki and about half of the local population

- lived in the Urakami district. It is said that about 10,000 Catholics were

killed by the atomic bomb. Although traditionally a rustic isolated suburb, the

Urakami district was chosen as the site for munitions factories in the 1920s,

after which time the population soared and an industrial zone quickly took shape.

The district was also home to the Nagasaki Medical College and a large number

of other schools and public buildings. The industrial and school zones of the

Urakami district lay to the east of the Urakami River, while the congested residential

district of Shiroyama stretched to the hillsides on the west side of the river.

It was over this section of Nagasaki that the second atomic bomb exploded at

11:02 a.m., August 9, 1945. The damages inflicted on Nagasaki by the atomic bombing

defy description. The 20 machi or neighborhoods within a one kilometer radius

of the atomic bombing were completely destroyed by the heat flash and blast wind

generated by the explosion and then reduced to ashes by the subsequent fires.

About 80% of houses in the more than 20 neighborhoods between one and two kilometers

from the hypocenter collapsed and burned, and when the smoke cleared the entire

area was strewn with corpses. This area within two kilometers of the hypocenter

is referred to as the "hypocenter zone." The destruction caused by

the atomic bomb is analyzed as follows in Nagasaki Shisei Rokujugonenshi Kohen

[History of Nagasaki City on the 65th Anniversary of Municipal Incorporation,

Volume 2] published in 1959. The area within one kilometer of the hypocenter:

Almost all humans and animals died instantly as a result of the explosive force

and heat generated by the explosion. Wooden structures, houses and other buildings

were pulverized. In the hypocenter area the debris was immediately reduced to

ashes, while in other areas raging fires broke out almost simultaneously. Gravestones

toppled and broke. Plants and trees of all sizes were snapped off at the stems

and left to burn facing away from the hypocenter. The area within two kilometers:

Some humans and animals died instantly and a majority suffered injuries of varying

severity as a result of the explosive force and heat generated by the explosion.

About 80% of wooden structures, houses and other buildings were destroyed, and

the fires spreading from other areas burned most of the debris. Concrete and

iron poles remained intact. Plants were partially burned and killed. The area

between three and four kilometers: Some humans and animals suffered injuries

of varying severity as a result of debris scattered by the blast, and others

suffered burns as a result of radiant heat. Things black in color tended to catch

fire. Most houses and other buildings were partially destroyed, and some buildings

and wooden poles burned. The remaining wooden telephone poles were scorched on

the side facing the hypocenter. The area between four and eight kilometers: Some

humans and animals suffered injuries of varying severity as a result of debris

scattered by the blast, and houses were partially destroyed or damaged. The area

within 15 kilometers: The impact of the blast was felt clearly, and windows,

doors and paper screens were broken. Wall clock found in Sakamoto-machi about

1 km from the hypocenter. The hands stopped at the moment of the explosion: 11:02

a.m. The injuries inflicted by the atomic bomb resulted from the combined effect

of blast wind, heat rays (radiant heat) and radiation and surfaced in an extremely

complex pattern of symptoms. The death toll within a distance of one kilometer

from the hypocenter was 96.7% among people who suffered burns, 96.9% among people

who suffered other external injuries, and 94.1% among people who suffered no

apparent injuries. These data show that the deaths occurring immediately after

the atomic bombing were due not only to burns and external injuries but also

to severe radiation-induced injuries. The late medical effects of atomic bomb

exposure include "keloid" scars, atomic bomb cataracts, leukemia and

other cancers and microcephaly (small head syndrome) due to intrauterine exposure.

Although aware that the atomic bomb had the power to instantly kill or injure

all people within a radius of four kilometers, the authorities were unable to

determine the death toll and number of injuries in Nagasaki. Still today there

is no accurate data on the number of people who died. A variety of factors contributed

to this lack of information, such as the paralysis of administrative functions

in the aftermath of the bombing and the inability of the postwar government to

initiate a proper investigation. Another obstacle was the enduring nature of

disorders related to atomic bomb exposure. A progressive increase can be expected,

therefore, at whatever point in time calculations are made. There are countless

cases of people who suffered injuries on August 9 and died after fleeing to areas

outside Nagasaki city and prefecture, only to be registered as dying of causes

other than the atomic bombing. Because of the lack of knowledge about radioactive

contamination, meanwhile, many radiation deaths were attributed to diseases.

The Nagasaki municipal government officially adopted the figure of "more

than 70,000" deaths on the basis of information from population surveys

and the estimate made by the Nagasaki City Atomic Bomb Records Preservation Committee

in July 1950. Said the committee in its report: "73,884 people were killed

and 74,909 injured, and 17,358 of the deaths were confirmed by post- mortem examination

soon after the atomic bombing." |

|

The

mushroom cloud seen from an American aircraft

The

mushroom cloud seen from an American aircraft Nagasaki

two days before the atomic bombing

Nagasaki

two days before the atomic bombing Nagasaki three days after the atomic bombing

Nagasaki three days after the atomic bombing  Photograph

by Hiromichi Matsuda

Photograph

by Hiromichi Matsuda Known

as Urakami, the district around the hypocenter (ground zero) area had been populated

for centuries by Japanese people of the Roman Catholic faith. At the time of

the bombing, between 15,000 and 16,000 Catholics - the majority of the approximately

20,000 people of that faith in Nagasaki and about half of the local population

- lived in the Urakami district. It is said that about 10,000 Catholics were

killed by the atomic bomb. Although traditionally a rustic isolated suburb, the

Urakami district was chosen as the site for munitions factories in the 1920s,

after which time the population soared and an industrial zone quickly took shape.

The district was also home to the Nagasaki Medical College and a large number

of other schools and public buildings. The industrial and school zones of the

Urakami district lay to the east of the Urakami River, while the congested residential

district of Shiroyama stretched to the hillsides on the west side of the river.

It was over this section of Nagasaki that the second atomic bomb exploded at

11:02 a.m., August 9, 1945. The damages inflicted on Nagasaki by the atomic bombing

defy description. The 20 machi or neighborhoods within a one kilometer radius

of the atomic bombing were completely destroyed by the heat flash and blast wind

generated by the explosion and then reduced to ashes by the subsequent fires.

About 80% of houses in the more than 20 neighborhoods between one and two kilometers

from the hypocenter collapsed and burned, and when the smoke cleared the entire

area was strewn with corpses. This area within two kilometers of the hypocenter

is referred to as the "hypocenter zone." The destruction caused by

the atomic bomb is analyzed as follows in Nagasaki Shisei Rokujugonenshi Kohen

[History of Nagasaki City on the 65th Anniversary of Municipal Incorporation,

Volume 2] published in 1959. The area within one kilometer of the hypocenter:

Almost all humans and animals died instantly as a result of the explosive force

and heat generated by the explosion. Wooden structures, houses and other buildings

were pulverized. In the hypocenter area the debris was immediately reduced to

ashes, while in other areas raging fires broke out almost simultaneously. Gravestones

toppled and broke. Plants and trees of all sizes were snapped off at the stems

and left to burn facing away from the hypocenter. The area within two kilometers:

Some humans and animals died instantly and a majority suffered injuries of varying

severity as a result of the explosive force and heat generated by the explosion.

About 80% of wooden structures, houses and other buildings were destroyed, and

the fires spreading from other areas burned most of the debris. Concrete and

iron poles remained intact. Plants were partially burned and killed. The area

between three and four kilometers: Some humans and animals suffered injuries

of varying severity as a result of debris scattered by the blast, and others

suffered burns as a result of radiant heat. Things black in color tended to catch

fire. Most houses and other buildings were partially destroyed, and some buildings

and wooden poles burned. The remaining wooden telephone poles were scorched on

the side facing the hypocenter. The area between four and eight kilometers: Some

humans and animals suffered injuries of varying severity as a result of debris

scattered by the blast, and houses were partially destroyed or damaged. The area

within 15 kilometers: The impact of the blast was felt clearly, and windows,

doors and paper screens were broken. Wall clock found in Sakamoto-machi about

1 km from the hypocenter. The hands stopped at the moment of the explosion: 11:02

a.m. The injuries inflicted by the atomic bomb resulted from the combined effect

of blast wind, heat rays (radiant heat) and radiation and surfaced in an extremely

complex pattern of symptoms. The death toll within a distance of one kilometer

from the hypocenter was 96.7% among people who suffered burns, 96.9% among people

who suffered other external injuries, and 94.1% among people who suffered no

apparent injuries. These data show that the deaths occurring immediately after

the atomic bombing were due not only to burns and external injuries but also

to severe radiation-induced injuries. The late medical effects of atomic bomb

exposure include "keloid" scars, atomic bomb cataracts, leukemia and

other cancers and microcephaly (small head syndrome) due to intrauterine exposure.

Although aware that the atomic bomb had the power to instantly kill or injure

all people within a radius of four kilometers, the authorities were unable to

determine the death toll and number of injuries in Nagasaki. Still today there

is no accurate data on the number of people who died. A variety of factors contributed

to this lack of information, such as the paralysis of administrative functions

in the aftermath of the bombing and the inability of the postwar government to

initiate a proper investigation. Another obstacle was the enduring nature of

disorders related to atomic bomb exposure. A progressive increase can be expected,

therefore, at whatever point in time calculations are made. There are countless

cases of people who suffered injuries on August 9 and died after fleeing to areas

outside Nagasaki city and prefecture, only to be registered as dying of causes

other than the atomic bombing. Because of the lack of knowledge about radioactive

contamination, meanwhile, many radiation deaths were attributed to diseases.

The Nagasaki municipal government officially adopted the figure of "more

than 70,000" deaths on the basis of information from population surveys

and the estimate made by the Nagasaki City Atomic Bomb Records Preservation Committee

in July 1950. Said the committee in its report: "73,884 people were killed

and 74,909 injured, and 17,358 of the deaths were confirmed by post- mortem examination

soon after the atomic bombing."

Known

as Urakami, the district around the hypocenter (ground zero) area had been populated

for centuries by Japanese people of the Roman Catholic faith. At the time of

the bombing, between 15,000 and 16,000 Catholics - the majority of the approximately

20,000 people of that faith in Nagasaki and about half of the local population

- lived in the Urakami district. It is said that about 10,000 Catholics were

killed by the atomic bomb. Although traditionally a rustic isolated suburb, the

Urakami district was chosen as the site for munitions factories in the 1920s,

after which time the population soared and an industrial zone quickly took shape.

The district was also home to the Nagasaki Medical College and a large number

of other schools and public buildings. The industrial and school zones of the

Urakami district lay to the east of the Urakami River, while the congested residential

district of Shiroyama stretched to the hillsides on the west side of the river.

It was over this section of Nagasaki that the second atomic bomb exploded at

11:02 a.m., August 9, 1945. The damages inflicted on Nagasaki by the atomic bombing

defy description. The 20 machi or neighborhoods within a one kilometer radius

of the atomic bombing were completely destroyed by the heat flash and blast wind

generated by the explosion and then reduced to ashes by the subsequent fires.

About 80% of houses in the more than 20 neighborhoods between one and two kilometers

from the hypocenter collapsed and burned, and when the smoke cleared the entire

area was strewn with corpses. This area within two kilometers of the hypocenter

is referred to as the "hypocenter zone." The destruction caused by

the atomic bomb is analyzed as follows in Nagasaki Shisei Rokujugonenshi Kohen

[History of Nagasaki City on the 65th Anniversary of Municipal Incorporation,

Volume 2] published in 1959. The area within one kilometer of the hypocenter:

Almost all humans and animals died instantly as a result of the explosive force

and heat generated by the explosion. Wooden structures, houses and other buildings

were pulverized. In the hypocenter area the debris was immediately reduced to

ashes, while in other areas raging fires broke out almost simultaneously. Gravestones

toppled and broke. Plants and trees of all sizes were snapped off at the stems

and left to burn facing away from the hypocenter. The area within two kilometers:

Some humans and animals died instantly and a majority suffered injuries of varying

severity as a result of the explosive force and heat generated by the explosion.

About 80% of wooden structures, houses and other buildings were destroyed, and

the fires spreading from other areas burned most of the debris. Concrete and

iron poles remained intact. Plants were partially burned and killed. The area

between three and four kilometers: Some humans and animals suffered injuries

of varying severity as a result of debris scattered by the blast, and others

suffered burns as a result of radiant heat. Things black in color tended to catch

fire. Most houses and other buildings were partially destroyed, and some buildings

and wooden poles burned. The remaining wooden telephone poles were scorched on

the side facing the hypocenter. The area between four and eight kilometers: Some

humans and animals suffered injuries of varying severity as a result of debris

scattered by the blast, and houses were partially destroyed or damaged. The area

within 15 kilometers: The impact of the blast was felt clearly, and windows,

doors and paper screens were broken. Wall clock found in Sakamoto-machi about

1 km from the hypocenter. The hands stopped at the moment of the explosion: 11:02

a.m. The injuries inflicted by the atomic bomb resulted from the combined effect

of blast wind, heat rays (radiant heat) and radiation and surfaced in an extremely

complex pattern of symptoms. The death toll within a distance of one kilometer

from the hypocenter was 96.7% among people who suffered burns, 96.9% among people

who suffered other external injuries, and 94.1% among people who suffered no

apparent injuries. These data show that the deaths occurring immediately after

the atomic bombing were due not only to burns and external injuries but also

to severe radiation-induced injuries. The late medical effects of atomic bomb

exposure include "keloid" scars, atomic bomb cataracts, leukemia and

other cancers and microcephaly (small head syndrome) due to intrauterine exposure.

Although aware that the atomic bomb had the power to instantly kill or injure

all people within a radius of four kilometers, the authorities were unable to

determine the death toll and number of injuries in Nagasaki. Still today there

is no accurate data on the number of people who died. A variety of factors contributed

to this lack of information, such as the paralysis of administrative functions

in the aftermath of the bombing and the inability of the postwar government to

initiate a proper investigation. Another obstacle was the enduring nature of

disorders related to atomic bomb exposure. A progressive increase can be expected,

therefore, at whatever point in time calculations are made. There are countless

cases of people who suffered injuries on August 9 and died after fleeing to areas

outside Nagasaki city and prefecture, only to be registered as dying of causes

other than the atomic bombing. Because of the lack of knowledge about radioactive

contamination, meanwhile, many radiation deaths were attributed to diseases.

The Nagasaki municipal government officially adopted the figure of "more

than 70,000" deaths on the basis of information from population surveys

and the estimate made by the Nagasaki City Atomic Bomb Records Preservation Committee

in July 1950. Said the committee in its report: "73,884 people were killed

and 74,909 injured, and 17,358 of the deaths were confirmed by post- mortem examination

soon after the atomic bombing."